Editor’s Note: The post below details an incredibly close call in the hills. We take safety in the backcountry seriously and hope the story James chose to share provides visibility and open dialogue about the inherent risks of certain adventures. For more information on mitigating avalanche risk, visit avitraining.org and kbyg.org.

The earth around me seemed to grumble and moan. At 19,000 feet above sea level, I instantly recognize the sound of tons of snow sliding down the mountain, taking anything and everything in its path. I looked up, my headlamp illuminating a rushing column of snow falling and draining into the crevasse above me. Jeremy was gone.

It felt like a bad dream— I tried to run, but moved in slow motion, the waist-deep snow sucking away my energy. The fear in the pit of my stomach was paralyzing, yet my body flew into a wild state of desperate motion. I started counting, knowing he had just a few minutes left to live. At that altitude, breathing is laborious. Connected by a 30m rope, I frantically pulled until there was no more slack. My heart lifted— found him! It’s leading right into the crevasse. My heart sank. I lost track of time, digging into the loose powder as best I could. My hands and feet were numb, but I gave it no thought. I finally felt something hard, about 4-5 feet down. Miraculously, his head was somehow on top, and I brushed away the snow. His face was a purplish white and he wasn’t breathing. How long had it been? Five minutes? Fifteen minutes? I yelled, screamed at him. I started giving mouth-to-mouth, pinching his nose shut with my frozen fingers. Still nothing.

Oh my god, he’s not waking up.

After hearing the stories of Yvon Chouinard’s and Doug Tompkins’ trip to Patagonia, I’ve dreamed of taking my own trip through the Americas, climbing everything I could along the way. Only this time, there was no old rickety Dodge van, just some old rickety Suzuki dual sports. To me, South America was where the deal got real, and after getting robbed our first two nights on the road in Colombia, we realized this wasn’t going to be a casual stroll through the park. With the exception of the robberies and the god-awful process of shipping our bikes across the Darien Gap, our experience was wonderful. Navigating through a Spanish-speaking continent is a real feat for a couple of east coast gringos. Crocodiles, coconuts, monkeys, and mosquitos— there were memories made around every corner.

From the very start of our Pan-Am ride, we carefully planned and timed our schedule around the climbing seasons. Mt Denali in early season, in order to make it down to the Canadian Rockies and East Sierras by late season, so we could climb in prime Joshua Tree season, to be able to climb Mexican Volcanoes late season… you get the point. We barreled through Central America and the northern part of South America to make it to Peru at the beginning of the season. Our sights were set on the Cordillera Blanca, an incredible range with some of the most dramatic mountains in the world. After a long, hard day of riding, I’ll never forget my first glimpse of the Andes.

“Thar she blows!” I shouted into our helmet comm system.

“Woohoo!” Allen yelled back. “It’s time to climb some mountains boys!”

The setting sun painted the mountains with oranges and pinks. I took a deep breath, thinking about the climbs and adventures to come. After riding and living in the jungle for the last while I couldn’t wait to taste thin air once again. We were finally in the Andes.

The stoke was high, and I instantly forgot about my cold and aching body. Most of our time in Latin America thus far had been spent in the jungle— hot, muggy, insect-infested, and pretty darn miserable. The jungle is captivating and beautiful but on a motorcycle? That’s a whole different story. Huaraz, our base camp for the next month, is a city informally known as “the Chamonix of the Andes”, and was located at 10,000 feet.

For some time, Allen’s knee had been swelling at a slow rate of speed. Upon arriving in Peru, his knee had swollen to damn near the size of a balloon, and due to the swelling it had made the last 1000 miles absolutely excruciating as he was unable to bend his knee and had to ride with his leg stretched out. After visiting the local clinic and finding out they didn’t have the slightest clue as to what was going on, we were left with no choice. We shipped Allen back to the states to get the medical attention he needed. It felt a bit like the fellowship of the ring was broken, but Jeremy and I decided to make the most of it and climb what we could until Allen’s return.

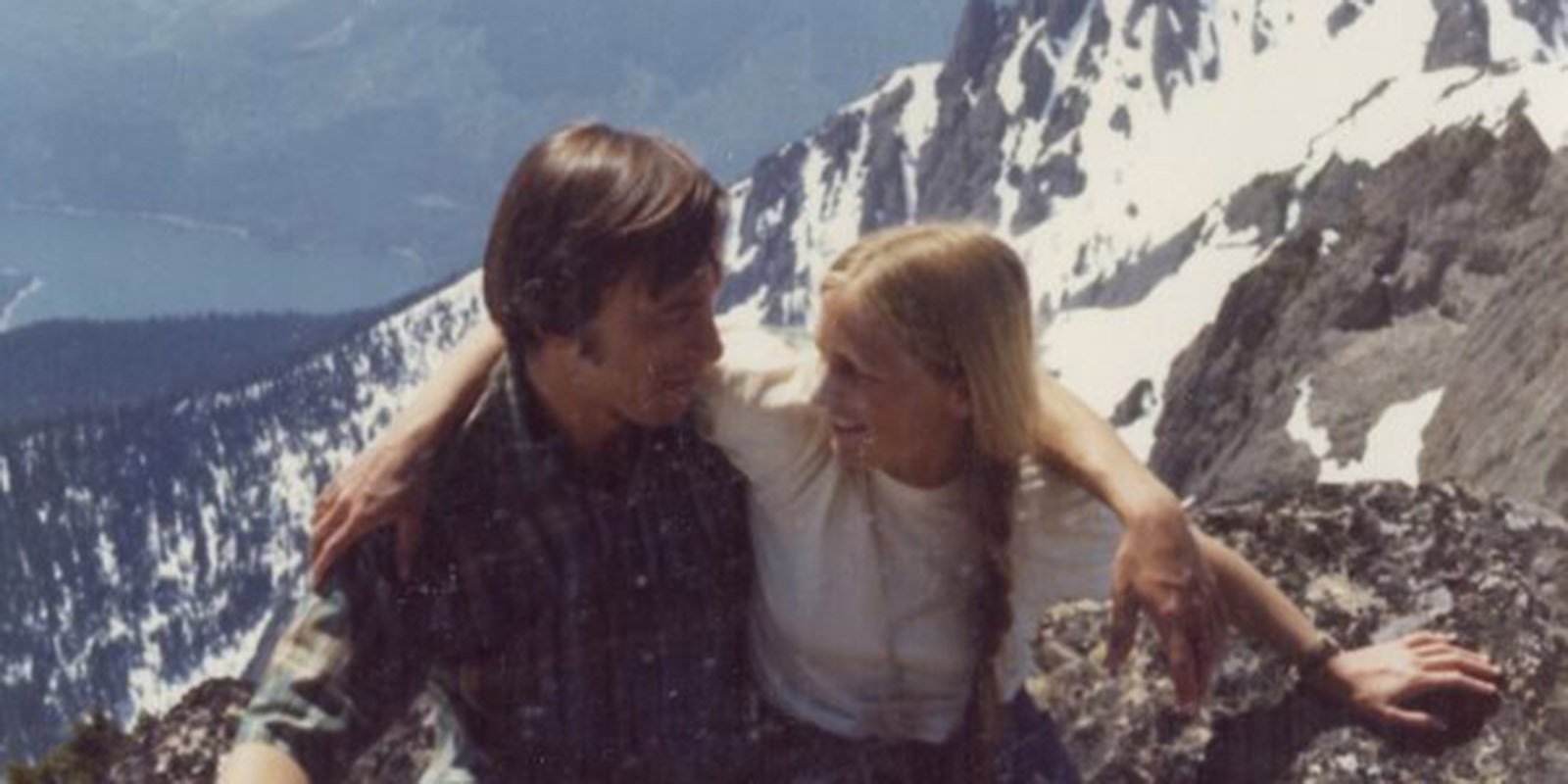

Allen’s knee infection turned out to be a strange case of Lyme disease, and after a couple uncertain weeks of strong antibiotics, he thankfully began his way back to health. While he was back home, Jeremy and I ripped out for a three-day climb of Nevado Pisco, a “small” acclimatization mountain of 18,871 feet. We got a kick out of what they referred to as small mountains. With so many 6000m peaks in the range, it truly made anything smaller look tiny in comparison. The altitude kicked our butts and I accidentally left the sunscreen at the trailhead, resulting in 2nd-degree burns, but our first climb in the Andes was one for the books. We left a gummy worm in Allen’s honor on the summit before starting the trek back town.

The weather looked hopeful for Chopicalqui, a 20,846 ft peak and one of the classic climbs in the Cordillera Blanca. Nobody had been able to summit as of yet, a couple teams getting shut down due to early season conditions. Jeremy and I had managed to make a tough first ascent of the season on Tocllaraju, a 6,034m D+ climb, and earned some street cred with the local climbing community and guide services. We figured we’d try to do the same on Chopi, which was supposed to be a grade or so lower. We packed what we needed, left our DR650s at the trailhead and began the approach to base camp. As always, I felt the familiar emotions of anxiety and anticipation. The weather thus far had been completely unpredictable and unstable, resulting in a few fatalities in the Blanca, but the adrenaline and excitement drowned out the fear of the unknown.

After acclimatizing for a day at base camp, we bumped up to high camp at 18,200 feet. The Huascaran massif, the tallest mountain in Peru and second tallest in South America, stood in perfect view. It was cold and stormy, with a system apparently moving in. We took a day to acclimatize, waking up the next morning only to be caught in a storm and full whiteout. We decided to wait another day and give it one more chance, as our food and fuel were running out.

We got an alpine start, hoping to be up and back before the sun rose in order to minimize avalanche and icefall danger. The alarms rang at 1 am, and the skies looked crisp and clear. I led for the first couple hours through steep and challenging terrain, at times nearly giving up and turning around due to deep snow. We finally gained the ridge and could see the silhouette of the summit against the clear night sky.

As I switched leads with Jeremy, he crossed a crevasse and yelled down for me to be careful when I got to it. That was the last thing I heard from him for the next few agonizingly long minutes. I’ll never forget the feeling of helplessness in those next moments. I’ve been in a number of near-death situations, but never something quite like this. Knowing your friend’s life is depending on your ability to think and act quickly is not a very nice experience.

We should have waited another day, I thought. Why didn’t we wait another day?! The longer I gave him mouth to mouth, the more my emotions swirled. I squeezed his nose and gave another puff. I slapped his face, yelled into his ear. He’s not waking up, it’s been too long.

Finally, he started breathing, ever so faintly. I kept with the mouth-to-mouth, and in a few minutes Jeremy woke up and took a gasp of air, coughing out snow. It took 15 minutes to dig him out, and as soon as he was free we hightailed it back down to High Camp.

Thinking back, there are things that we could have done differently, but there are also plenty of things that happened perfectly— the crevasse stopping the slide, the position of Jeremy’s head, if it had broken just a few minutes later, the list goes on. Every time I head into the mountains, I’m aware of the risk and usually keep the idea of it in the front of my mind but push the reality of it to the back. Finally, I guess we had pushed a little too far, a little too close to the edge. Toyed with the fine line.

“A real adventure is something you might not come back from.” The words of Yvon Chouinard pose an interesting question. “At what point are the stakes too high? At what point is it simply not worth it? Am I willing to die— for this?” If there’s one thing that I’ve learned from processing these sort of questions, it’s that it can help structure an attitude of intentionality and gratitude. I see the world through a slightly different lens, constantly reminded not to take life, friends, or anything for granted.

To catch up on the Pan American Trail adventure, head to “Staring Down The Long Road” to hear about the start of the journey and the crew’s time on Denali. Then read “Climbing and Risk” about the crew’s journey up the imposing Mt. Robson and their balance of climbing and riding “Southbound.”